The Bible exhorts us to “be hospitable”. Interestingly, Tamil culture places a high premium on the concept of Virunthombal (Hospitality). Classical Tamil literary texts highlight the many noble aspects of hospitality and extoll its role in the life ethics of Tamil society.

Christian hospitality must be Biblically illumined and culturally rooted in practice and reflection. The practice of Tamil-Christian hospitality can significantly benefit from a creative encounter and/or exchange between Biblical and cultural texts/traditions.

In this article, I seek to explore such possibilities of a ‘double enrichment’ through the “fusion of horizons” for the practice of hospitality both as individual Christian families and as a Church (family of families).

What does Hospitality mean?

In general, hospitality is being friendly, generous, welcoming and entertaining guests. However, this is a simplistic understanding of hospitality.

The cultural concept of Virunthombal (Hospitality) and the Biblical teaching on Hospitality (as we shall see) are not limited to such a simplistic understanding. In fact, hospitality is more than offering a cold drink and serving a hot meal.

Let us briefly look at the understanding of hospitality within Tamil culture and Biblical teaching.

Hospitality within Tamil Culture

The Tamils are known for their splendid hospitality. The traditional picture of hospitality includes

- greeting with folded hands (Vanakkam),

- comfortable and convenient stay,

- delicious meals with a variety of dishes in traditional banana leaf

- a group visit to places of worship or entertainment

- and a send-off with gifts for a long list of (extended) family members as well.

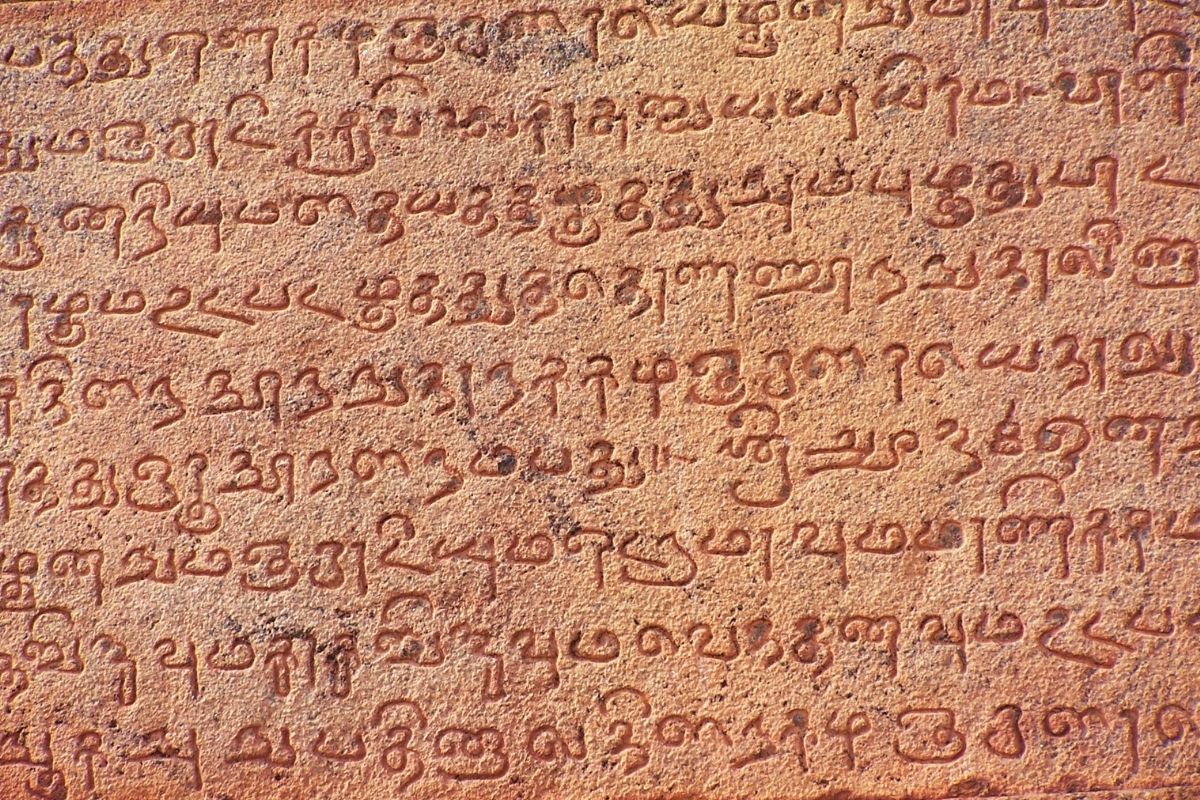

Tamil Literary works: A Treasure trove of references

The concept of virunthombal (Hospitality) cannot be limited to sharing a meal or providing a comfortable stay. The idea is rife with many other impressive features outlined in Tamil literary works.

Tamil is one of the oldest languages in the world. It has a rich repository of literary works. These works of antiquity are a treasure trove of references to Tamil cultural conventions, social customs, and ideological concepts.

There are many interesting references in literary works such as Sirupaanaatrupadai’, Four hundred Poems (Purananuru), and The Sacred Couplets (Thirukural). These works present a multi-dimensional concept of hospitality (Virunthombal) within the wider Tamil culture.

Hospitality: The very ethos of Tamil culture

Sirupaanaatrupadai’ focuses on the tradition of hospitality (virunthombal) extended to guests, and The 400 heroic Poems (Purananuru) delineate hospitality shown to strangers.

The two literary works of antiquity highlight numerous instances of hospitality extended to poets, travelling dance-drama troupes, performing artists, and travellers by both wealthy patrons and ordinary people.

Through these numerous references, one can easily find that Hospitality (Virunthombal) was ingrained in the very ethos of the cultural life of the Tamils.

Hospitality as the ultimate purpose of life

“The Sacred Couplets” (Thirukural) is a secular treatise. It is an influential text revered as an ultimate guide for ethics and morality. Interestingly, the poet-Sage dedicates an entire chapter to hospitality.

According to the great sage, Hospitality is “the purpose of nurturing wealth and leading a family life” (verse 81). Wealth and family life find their true meaning only in the practice of hospitality. Hospitality is an absolute wealth (verses 84, 89), beneficial (verse 87) and spiritual action (verse 88). Moreover, he says, “the one who is hospitable and awaits the next guest when the present guest leaves will be a welcome guest in heaven”(v86).

Hospitality for the stranger

Hospitality was reserved for both uravinar (close or extended family members) and virundhinar (strangers). The hospitality to strangers (virundhinar) was extended through ‘spatial design’ and ‘dining spaces’ purposefully created with the ‘stranger’ in mind.

Traditionally, ancestral houses had thinnai (Verandah or raised platforms) adjacent to the house facing the street. These were meant for long-distance travellers to spend the night and leave in the morning. The strangers were also offered food and water to refresh and continue their journey.

Besides, food was served to travellers, cultural artists and even strangers in dining spaces (annasathirams). Free accommodation (without any time restriction) was provided in guesthouses (sathirams) run by wealthy patrons all along major roads linking villages to towns.

The Biblical Teaching on Hospitality

The concept of Hospitality is found both in the Old and the New Testaments. Due to space limitations, I will primarily focus on hospitality in the New Testament.

Jesus and Hospitality

Hospitality is an important theme of the Gospel accounts. Jesus accepted hospitality even as he extended it to others.

Jesus (and his disciples) often stayed with those who welcomed him – Peter (Mk 1: 29 – 31), Matthew (Mt. 9: 10 – 17), Martha (Mk 10:38), Simon, the Pharisee (Lk. 7:36 – 50), and Zacchaeus (Lk 19: 1 -10).

He accepted gifts given by Mary Magdalene, Joanna, Susanna and many others who provided for him out of their means (Lk 8: 1 – 3). Interestingly, Jesus even extended hospitality to individuals (and groups as well).

In John’s Gospel account, we read of Jesus’ invitation to two disciples of John to stay with him. They stayed with him the whole day (Jn 1: 39) and enjoyed the fellowship. Similarly, the choosing of the twelve disciples was an invitation to “be with him” (Mk. 3:14).

The feeding of the multitude in Bethsaida (Mk 6:30 – 46; Lk 9:10 -17) and the region of Gerasenes (Mk 8: 1-9; Mt. 15: 32 – 39) is also an act of hospitality.

Interestingly, Jesus invited the crowd to sit down (Mk 6:6), asked the disciples to serve food (Mk 6:7) and satisfied their hunger (Mk 6:8).

Hospitality to the outsider

Jesus’ table fellowship (Mt. 9:10) is an expression of inviting the estranged people (The poor, Tax collectors and Sinners) to be part of the disciples. Due to dietary considerations, it was not customary for Jews to eat with strangers.

And yet, Jesus frequently engaged in ‘inter-dining’ to include the ‘outsider’ like family (Lk. 14: 12 – 14).

The practice of multi-dimensional hospitality in the Early Church

The Early church practised hospitality and developed a reputation for love and service. Worship consisted of the Love feast (Agape meal), a communal meal shared among Christians (cf. I Cor. 11: 17 – 34).

Besides, the New Testament writers exhort congregations to practice hospitality as an expression of loving and serving one another (1 Peter 4: 8 -9; Heb 13:16).

Hospitality is seen as a leadership quality (1Tim 3:2; Titus 1:8), an essential good work (1Tim 5:10), serving travelling ministers (Rom. 12:13; 3 Jn 1: 5 – 8; Rom.16:23; Acts 28:7) and as acceptance (Acts 16:15).

Serving Jesus in serving the least of men

The Bible encourages all Christians to continue “brotherly love” and practice hospitality without grumbling (1 Pet. 4:9). Hospitality is also to be extended to our enemies (Rom. 12: 20), the household of faith (Gal 6:10), and strangers (Heb 13:1-2).

Hospitality to strangers provides an occasion to serveangels. (Heb 13: 1 -2). Moreover, the practice of hospitality – feeding the hungry, clothing the needy, and visiting prisoners – becomes an occasion to serve Jesus (Mt. 10:40 -42; Lk. 24: 44 – 45)

Text/Tradition and Theology: Towards encounter and exchange

The Biblical text and the Tamil Literary texts/tradition have many things to say about hospitality. Most importantly, they have a lot to say to each other.

Hospitality is at the heart of Tamil culture. It is greatly valued and revered as a cultural duty and societal obligation. In the Biblical tradition, it is an essential good work that demonstrates Christian character and leadership quality.

Both traditions do not limit hospitality to sharing meals and offering a comfortable stay. They present hospitality as a multi-dimensional concept. The texts expand the scope of hospitality by including the ‘stranger’. In Tamil culture, hospitality is not just for family guests (uravinar) but also for the Stranger-guests (Virundhinar).

Likewise, the Bible promotes a multi-dimensional concept of hospitality and, in particular, exhorts us to be hospitable to the ‘stranger in our midst.

Additionally, it presents the radical idea of hospitality towards the “outsider” and even the “enemy”. Jesus’ ‘inter-dining’ with ‘outsiders’ is quite revolutionary, and the “samapandhi virundhu’ (A feast for all social classes) is something that Tamil society needs to consider seriously.

Tamil hospitality, particularly to the stranger, is known by the famous refrain: “Vandhavarai Vazha Vaikkum Tamizhagam” (The Tamils help the stranger live and prosper).

In the Bible, Hospitality to the stranger is emphasised with a constant memory recall of Israel’s experience in Egypt (Lev. 19 and Deut. 10). Hospitality includes access to livelihood, privileges and rights for the stranger/Alien.

Tamil culture emphasises the family (the husband-wife team) serving guests/strangers. The New Testament exhorts congregations (?) – the family of families – to practice hospitality as an expression of love and service to one another.

The New Testament does not expand on the teaching of hospitality. It delineates Jesus’ practice of hospitality and best leaves it to congregations re-imagine hospitality and seek contextual applications.

Tamil cultural texts are replete with descriptions of the practical application of everyday hospitality in the homes of ordinary people and by creating ‘living spaces’, ‘spatial design’ and ‘food-houses’. Such engagements can help unfold the Biblical teaching on hospitality ‘creatively’ within the wider culture.

The ‘doubly-enriched’ Christian Hospitality

The Bible illumines the cultural practice of hospitality, and the cultural aspirations provide opportunities for the practice of biblical hospitality. The understanding of Christian Hospitality, then, is ‘doubly’ enriched.

Hospitality is more than offering a cold drink or hot meal. The sharing of the meal is not merely to satisfy the hunger (or a need) but rather a practical application of love-in-action. And therefore, the practice of hospitality is not culturally conditioned but spiritually inspired.

The invitation to share the meal with the ‘stranger’ ( even one’s enemy) is no longer a cultural obligation but a genuine expression of love for the ‘other’. Christian hospitality, then, includes even the “outsider” and the “enemy” in our family/community.

Hospitality, then, becomes the starting point for the free flow of conversation, the meeting of hearts, and sharing of lives. Feeding the hungry, clothing the needy, and visiting prisoners – becomes an occasion to serve Jesus (Mt. 10:40 -42; Lk. 24: 44 – 45)

Secondly, Christian hospitality is an act of service to one another in humility. Hospitality is not merely a sign of abundance but rather an act of humility. Hospitality – serving one another in humility – is an essential attribute of Christian character.

Thirdly, the understanding of ‘familial relationships’ and ‘living spaces’ in terms of hospitality within Tamil culture opens avenues for missional living. Often, Hospitality provides a first-hand experience for many to know who we are. Our living spaces and dining spaces have the potential to be “missional” places. Hospitality, then, becomes the sharing of our faith (without words).

The Bible and culture have a lot to say about life and, more importantly, to each other. I have explored the concept of ‘double enrichment’ of Christian life and witness through ‘an encounter and/or exchange between the Biblical teaching on hospitality and Virunthombal (hospitality) idea within Tamil culture.

A creative dialogue between the Bible and Tamil literary texts can enrich the practice of hospitality by Tamil-Christians. Hopefully, Christians in the Global South will seek creative avenues for the ‘double-enrichment’ of our life and witness. Our voice and wisdom must be heard.